New climate change report suggests dire effects in Mid-Atlantic

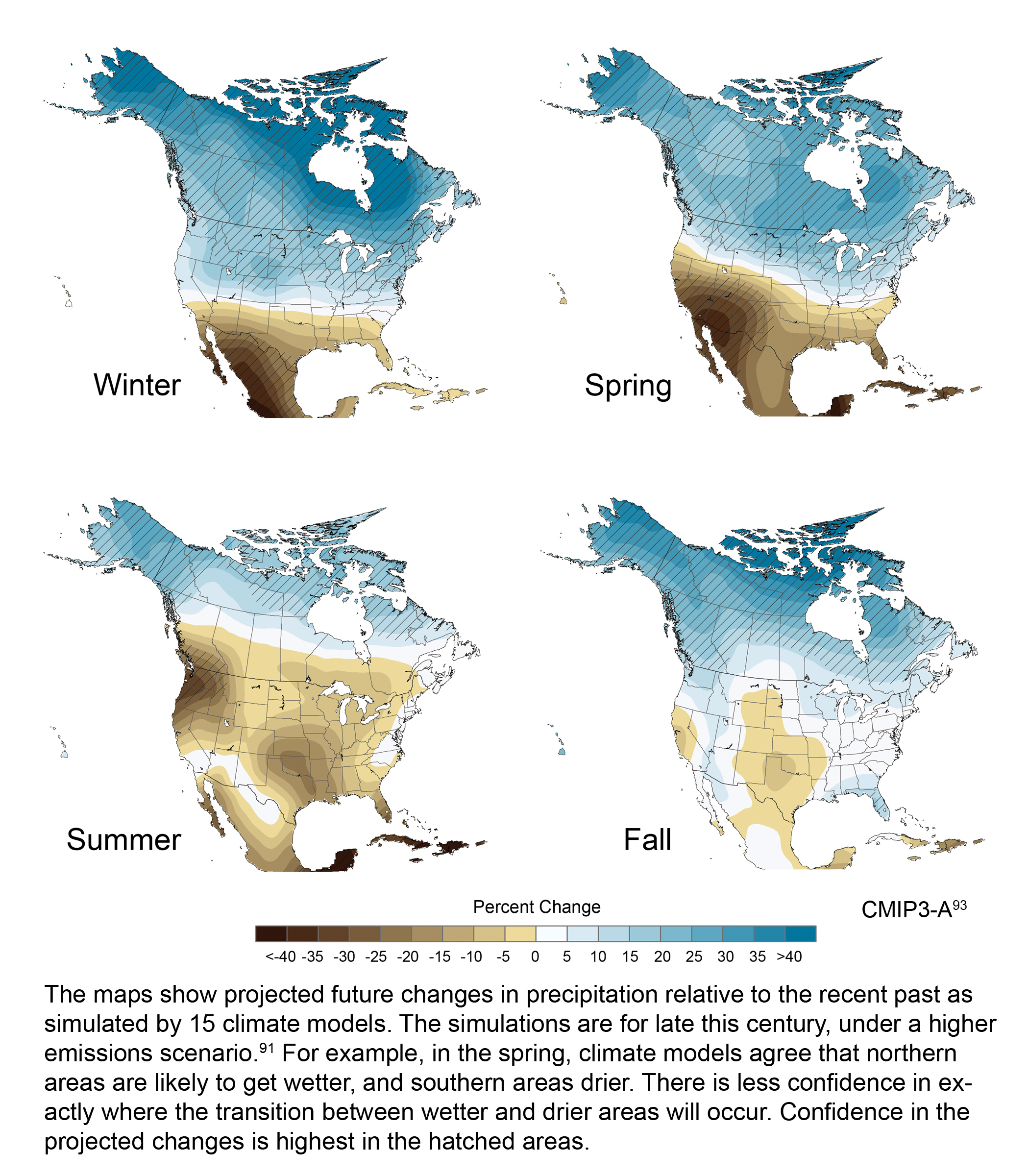

Changes in seasonal precipitation patterns in North America. (U.S. Global Change Research Program)

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. — “Human-induced climate change is a reality, not only in remote polar regions and in small, tropical islands, but in every place around the country — in our own backyards. Climate change is happening. It’s happening now.”

So said Dr. Jane Lubchenco, undersecretary of Commerce for Oceans & Atmosphere and NOAA Administrator, at a White House news conference Tuesday announcing the release of the report Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. The report documents evidence of climate change effects in the United States today, discusses projected effects over the next century, and offers a breakdown by region — including the Mid-Atlantic.

The report contains little information new to those who have followed the climate change debate over the years, it marked the first time since President George W. Bush’s inauguration in 2001 that the White House has unequivocally stated that humans are driving much of the climate changes documented today.

Jonathan Hoekstra, director of the Climate Change Program at The Nature Conservancy, summarized the importance of the report.

“This report paints the clearest picture yet of the risks that climate change poses to the United States — our infrastucture, our water supplies, agriculture, energy, health, and ecosystems,” Hoekstra said. “Impacts have often seemed far off and in someone else’s backyard. No more. If we don’t take decisive action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, too many of these risks will become realities.”

Aaron Huertas of the Union of Concerned Scientists offered a similar assessment.

“While the studies cited in the report aren’t new, the assessment process is an opportunity to identify the most important effects climate change could have on the United States,” Huertas said. “If anything, this report served to further underscore the differences between a future with unchecked climate change and one in which emissions — and resulting temperature increases — are greatly reduced.”

Climate Change Report Links:

Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States

Watch the White House press conference announcing release of the report

The report is required by the Global Change Research Act of 1990. The law established the U.S. Global Change Research Program and mandated that national assessment reports detailing current and potential climate change effects on the U.S. be produced every four years. The first report was produced by the Clinton administration in 2000, but the Bush administration — noted for its skepticism on climate change matters and allegations of trying to muzzle scientists researching climate change issues (allegations backed by documents, by the way) — was sued by environmental groups its failure to produce the next scheduled assessment in 2004.

The Bush administration lost. It released a first draft of what became the current report in 2008 as ordered by the court.

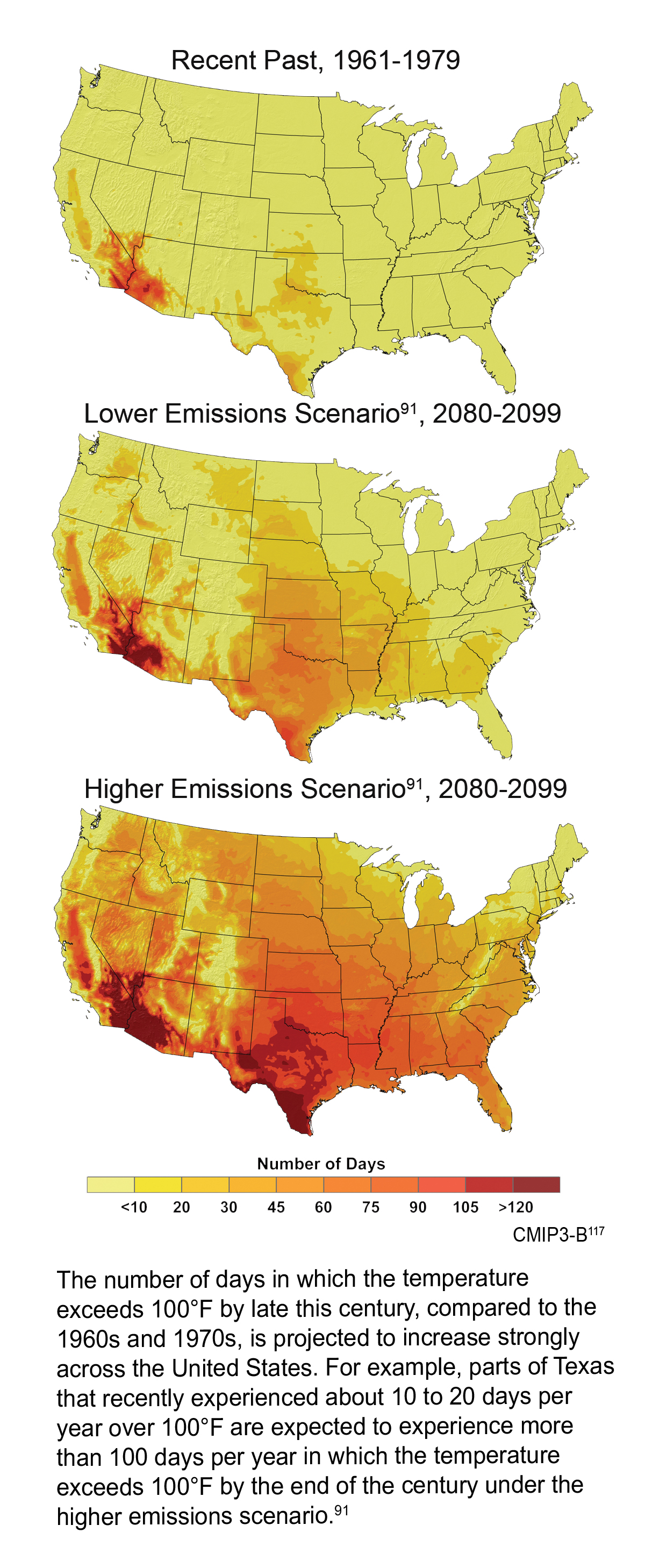

Among the overall findings of the report, it says that average temperature rise in the United States has followed the global trend, with a 1.5°F increase since 1990 and an additional increase of 2°F to 11.5°F by 2100. Without the human contribution in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and other temperature drives, global average temperatures would have cooled slightly since the 1950s. The higher temperatures will lead to decreased demand for energy for heating, but increased demand for energy for cooling. Urban residents are very vulnerable to heat-related illnesses and deaths as a result of rising temperatures.

Projected number of days with temperatures greater than 100 degrees by the end of the century. (U.S. Global Change Research Program)

Southern states will see a decrease in precipitation amount, northern states will see an increase. Seasonal precipitation patterns will change, too, with almost all of the Lower 48 states seeing a decrease in summer precipitation amount. Much of the nation has already seen an increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events. Changes in precipitation patterns will affect water supplies and hydropower production in some regions.

Ecosystem effects are already being felt. Among those effects are changes in ecosystem functions such as decomposition and nutrient cycling, in geographic distribution of species, in timing of migrations, in disturbance (such as wildfire) regimes, in pest and disease outbreaks, and in invasions by non-native species. Agricultural ecosystems will be similarly affected.

The Mid-Atlantic region is split in the report: Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania are in what the report describes as the Northeast, while North Carolina and Virginia are in the Southeast. What are the key findings for the region? It depends.

“It depends on who you are and what you do,” Huertas said “People who plan on deriving much of their income from agricultural products such as cranberries and some types of apples need to think about a long-term plan for switching to other crops or seeing reduced yields as frost days decline. Some ski resorts in the Northeast will be tenable, while others might not be. Coastal cities especially will have to watch out for sea level rise. And cities such as Philadelphia and New York will have to deal with potential sewage system overflows due to higher precipitation. There are many more examples, but the basic nature of climate change is that it alters fundamental aspects of our life and society we take for granted.”

In the northern portion of the Mid-Atlantic, winter temperatures have risen twice as much as the annual average — 4°F as opposed to 2°F since 1970. More frequent hot days (over 90°F), longer growing seasons, increased incidence of heavy precipitation events and a shift in winter precipitation from snow to rain (leading to earlier melt of snowpack) have been observed over much of the region. In the southern portion of the Mid-Atlantic, fall precipitation has increased somewhat, but summer precipitation has decreased — leading to an increased incidence of summer drought the past three decades.

In the future, warmer conditions will render much of the region unsuitable for crops long associated with it, such as apples, blueberries, and cranberries. The dairy industry will likewise be adversely affected, as will the maple syrup industry as maple/beech/birch forests are displaced to the north by oak-hickory forests. The shorter winters and decreased snowpack will likewise adversely affect the winter sports industry throughout the region.

Toward the south, higher summer temperatures and lower summer precipitation will trigger a rise in heat-related illnesses, higher heat indexes and greater demand for energy to cool homes and businesses. Roads will be affected, as the hotter temperatures will lead to more frequent buckling of pavement on roads and possible warping of rails leading to derailments. As soil moisture is depleted, crops will suffer.

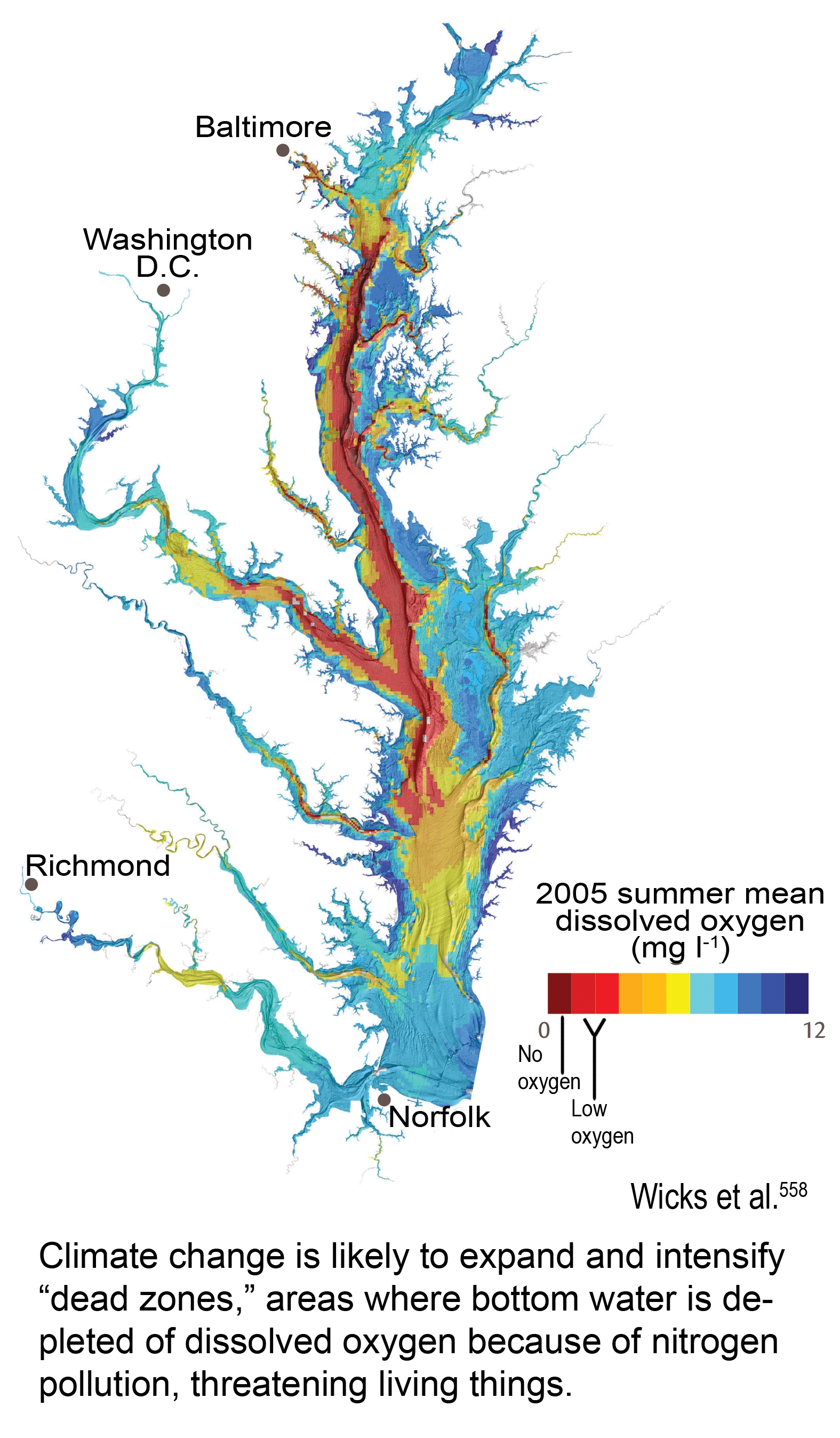

Climate change will likely lead to expansion of Chesapeake Bay dead zones. (U.S. Global Change Research Program)

Coastal areas will have to cope with rising sea levels, which contribute to shoreline erosion and loss of coastal wetlands and real estate. Coastal development will be more vulnerable to higher storm surges. Rising water temperatures will likely trigger an increase in the frequency and intensity of tropical storm systems. Increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is making the oceans more acid, which makes it more difficult for shellfish to extract from the water the carbonate minerals they use to make their shells. The combination of higher water temperatures and increased spring runoff will lead the expansion of oxygen-depleted “dead zones” in coastal waters like the Chesapeake Bay. Warmer waters will also lead to a northward shift in the geographic distributions of some marine organisms — such shifts are already under way.

Despite the dire outlook for the region, Huertas finds room for hope.

“I can tell you that the Mid-Atlantic region has been a leader in adopting renewable electricity standards, clean car standards and even a cap-and-trade system for power plants,” said Huertas. “Members of Congress are now considering climate and energy legislation based in large part on success Northeast states and Mid-Atlantic states have had with this type of policy. Hopefully, the United States can take the same leadership role in the world as the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states have assumed in the U.S.”

— David M. Lawrence

EDITOR’S NOTE: An earlier version of this story was posted without the comment by Jonathan Hoekstra of The Nature Conservancy, who had not have time to respond by the time of the original post. The story was revised to incorporate his statement.

DISCLOSURE: The editor, David M. Lawrence, occasionally volunteers for The Nature Conservancy, the organization for whom the source Jonathan Hoekstra works.

Leave a Response

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.