Mysterious bat disease forces closure of caves, mines

Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) with fungus on its nose. (Ryan von Linden/New York Department of Environmental Conservation)

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. — The USDA Forest Service closed caves and abandoned mines throughout the southeastern United States last week in an effort to stem the spread of white nose syndrome among bats, a disease characterized by the appearance of a white fungal growth on the muzzles, ears, or wing membranes of infected bats.

The fungus that is associated with the syndrome (Geomyces sp.) thrives in the dark, cool conditions of the caves where the affected bat species hibernate. Infected individuals consume the fat reserves they need to during hibernation too quickly and starve. Mortality rates of 75 percent are common, but as many as 95 percent of bats in some colonies have died after the disease appeared.

According to the U.S. Forest Service, as many as 500,000 bats have died in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states in the three years since the disease appeared. Of that total, 25,000 have been the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis), an endangered species.

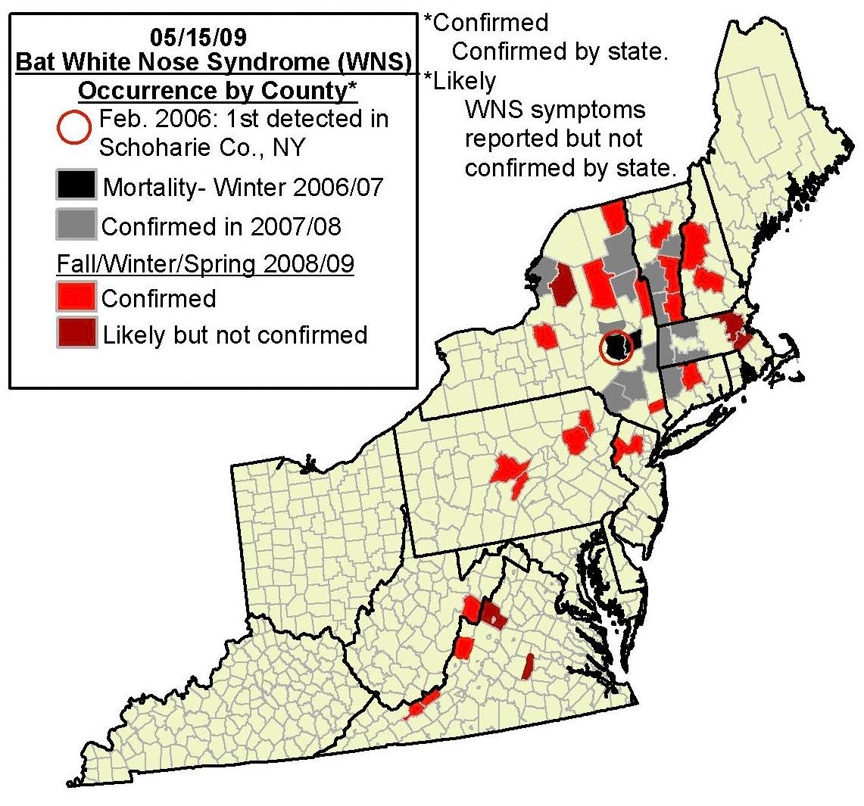

White nose syndrome was first observed among a bat colony at Howes Cave, near Albany, N.Y., in February 2006, the disease has spread to north and east to colonies in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont; and south as west to colonies in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Evidence suggests that humans as well as bats play a role in spreading the disease. Humans — by harboring fungal spores on shoes, clothing, or equipment — may inadvertently transport the fungus from cave to cave. This concern has led to the strategy of closing caves and other underground refugia, such as abandoned mines, that bats may inhabit.

On April 24, the Eastern Region of the Forest Service closed caves and mines in a swath of northern states from Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri east to Maine. The Eastern Region includes West Virginia, where White Nose Syndrome has been confirmed from several caves in Pendleton County.

White Nose Syndrome Links:

USFWS Northeast Region

USGS Fort Collins Science Center

USGS, National Wildlife Health Center

Bat Conservation International

National Speleological Society

The Southern Region followed suit on May 21 with the closing of caves from Oklahoma and Texas east to Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. The Southern Region’s closure will be in effect for at least a year. So far, Virginia is the only state within the region to have confirmed cases of white nose syndrome — from caves in Bath, Bland, and Giles County. There is evidence to suspect cases from Rockingham and Cumberland Counties as well.

The Cumberland County case is anomalous in that the county, which is on the Virginia Piedmont, has no caves. There may be old mines, however, where bats may hibernate.

Other federal and state agencies, as well as private landowners and organizations involved in either bat conservation or cave exploration, have joined or are cooperating with the cave and mine closure effort.

— David M. Lawrence

Leave a Response

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.