Review: Shooting in the Wild

Chris Palmer

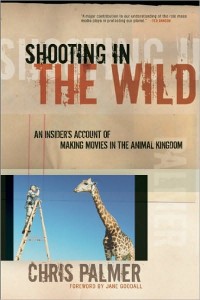

Shooting in the Wild: An Insider’s Account of Making Movies in the Animal Kingdom

San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2010

ISBN: 978–1‑57805–148-91. 223+xxiii pp. $24.95 (US)

MECHANICSVILLE, Va. — On September 22, an article in The Washington Post touched off a vigorous discussion on ECOLOG‑L, a popular scientific listserv sponsored by the Ecological Society of America, about “naturefaking” in environmental films and documentaries. The story, which appeared under the somewhat misleading headline, “Wildlife filmmaker Chris Palmer shows that animals are often set up to succeed[1],” discussed some of the issues raised in Palmer’s new book, Shooting in the Wild: An Insider’s Account of Making Movies in the Animal Kingdom.

Shooting in the Wild is no confessional. It is no polemic. Palmer, Distinguished Film Producer in Residence at American University’s Center for Environmental Filmmaking, offers a reasoned, nuanced view of the realities of filming the world’s animal life. The book begins with an introduction that illustrates the power of nature films. Palmer tells the story of Bruce Weide, an Alaskan who as a youth was steeped in the mythology of the evil wolf. He eagerly took part in hunts for wolves—in part to earn the $50 bounty for wolf pelts paid by the state. But shortly after seeing a Canadian film, Death of a Legend, that portrayed wolves as efficient predators but also loyal and affectionate members of extended families, Weide found that he could not shoot a wolf framed neatly in the crosshairs of the scope of his rifle. Weide eventually became a filmmaker himself. He has spent years working tirelessly to change public opinion about wolves.

The next section of Shooting in the Wild surveys the art, history, and method of nature filmmaking. Beginning with a discussion of the diversity of nature films—from television to IMAX—Palmer surveys the historical development of nature films as they evolved from entertainments featuring a highly distorted vision of reality (assuming there was much reality to begin with), to more high-minded productions featuring strong conservation messages, to the confused mix we have to day of very informative programs mixed with extremely exploitative tripe (my words, not Palmer’s).

The method section recaps the procedure of making wildlife films—from developing the concept, obtaining funding, building a crew, working with experts, scouting locations, shooting, post-production, marketing, distribution, and outreach. The section includes chapters on funding and working with celebrities.

The heart of the book addresses the ethical dilemmas one encounters in nature films. No filmmaking is easy, but Palmer points out that filming nature is especially challenging. Animals and plants carry on their lives on their schedule, not ours. If a filmmaker is interested in coral reproduction, he had best be in the water with dive gear, camera gear, and lights on the one or two nights out of the year when corals spawn. Animals and plants live in their neighborhood, not ours. A filmmaker interested in the life cycle of ancient Atlantic white cedar best not be afraid of heights—more than that, he best be a good rock climber because most of the old-age trees live on steep cliff faces. Animals and plants are adapted to the hazards and nuisances of their environment, not ours. A filmmaker trying to capture hunting behavior of the northern lynx had better be prepared for vicious attacks by mosquitoes and black flies in the summer and for extremity-destroying cold in winter.

A range of other challenges can make life hell for a nature filmmaker. Large, dangerous animals are best filmed from a distance, where long lenses can adequately capture the images, but nothing can adequately capture the sound. Rare animals may be too difficult to find, or may be too vulnerable to disturbance, in the wild. Many organisms are too small to be seen, much less filmed, without specialized equipment. These are just a small subset of the pitfalls of making nature films.

Nature filmmakers from the time of pioneers such as Jean Painelevé have resorted to a number of devices to get the proverbial and actual shot. These include the use of captive animals, enclosures, artificial sound, staged encounters, and computer graphics. For example, an episode in the BBC television series Planet Earth featured a sequence in which a mouse lemur hunts giant hawk moths seeking nectar in the flowers of a baobab tree. The lemur feeding sequence appears to be shot in an enclosure—remarkable, well-lit (for a night scene) close-ups and the scarcity of discernable shapes, such as from adjacent foliage, in the background of what is supposed to be a forest canopy at night suggest to an experienced field researcher such as myself that no forest was present. (A suggestion is not proof, however.) Whether or not the producers of Planet Earth shot the sequence in the field or in a lab, it is the kind of shot that would more easily be obtained in an artificial setting.

According to Palmer, filming in artificial or restricted settings posed three primary ethical concerns: 1) scientific accuracy, 2) animal welfare, and 3) deception of the audience.

Given the feeding frenzy for every scrap of profit modern media organizations face, scientific accuracy is sometimes sacrificed. Emphasis on animal sex and violence—such as in Animal Planet’s dreadful Untamed and Uncut—titillate rather than enlighten viewers by offering the illusion of prevalent nature of what are truly rare encounters. In such programs, the role of humans in provoking animal attacks is often downplayed to feed the narrative theme of the savagery of nature. While the footage in Untamed and Uncut is often real (though appropriate context is omitted), other programs often feature captive animals trained to provide the appropriate—and exaggerated—violent response. Nevertheless, scientific accuracy, is often the easiest of these three ethical issues to address. By thorough research and consultation with scientific experts, scientific accuracy of the scenes can be assured. The concept of scientific accuracy, however, is often used to justify filming under conditions that are arguably unethical otherwise.

For example, scientific accuracy is often used as the justification for footage obtained from the use of captive animals that are not properly cared for. Many filmmakers, Palmer included, often use wild animals reared in game farms to obtain footage that is all-but-impossible to obtain in the wild—such as parenting behavior of secretive predators such as wolves or social behavior of burrowing animals such as naked mole rats. While many operators of game farms work hard to ensure the welfare of the animals in their care, many unfortunately do not, either keeping animals in conditions that are unhealthy or abusing animals that don’t perform “properly.” Wild animals handled by filmmakers or scientists, or whose movements are temporarily restricted (such as by enclosures), often face undue stress—not that life in the wild is not stressful enough.

Many field scientists realize the effect their research has on their subjects and work hard to ensure that such stress is minimized and that the scientific benefit derived from the research is worth the harm done to a small sample of individuals.[2] Most animal research proposals, as with most human research proposals, are screened by institutional review committees before such research is begun. The goal of such review is to ensure that the methods are scientifically defensible, i.e., that they are necessary and likely to get the desired results, and that no less-intrusive method can adequately substitute for the proposed research approach. No similar system of review exists for nature filmmakers, but Palmer suggests the filmmaking community should consider establishing one. He strenuously argues that welfare of the animals should be the top priority of any nature filmmaker.

Viewers of wildlife films often expect every scene to be shot in the wild and every sound to be recorded in the wild. For a variety of reasons, this is not practical. In his book, Palmer recounts an incident in which his wife called him “a big fake” when she found out that the sound of a grizzly bear splashing through a stream in one of his documentaries was actually the sound of a person splashing his hands in a basin of water. While the sound effect accurately reflected the sound of a bear walking through water, the use of such sound effects arguably deceives the audience. Other arguably deceptive techniques in nature films include the use of footage shot inside enclosures or other controlled conditions, the use of computer-generated imagery (CGI), the use of story lines that purport to follow animal characters that are actually composites of different individuals filmed at different times and/or different places.

While viewers may feel cheated when they learn of such techniques, filmmakers often have excellent reasons to use them—to minimize harm to wild animals, to capture behavior that would be impossible to capture in any other way, to just have sound to go with the images. (With a zoom lens, it is relatively easy to get a good image of a grizzly bear from a distance, but even with shotgun and parabolic microphones, it is all-but-impossible to get good sound from a distance.) Although most of the ethical burden is on the filmmaker, viewers who feel deceived by the use of such techniques should ask themselves if they would watch a film that does not include such devices.

For Palmer, the dilemma is as old as filmmaking itself, and each filmmaker has to decide for himself or herself what approach is appropriate, whether the shots to be gained are worth the ethical compromises involved. In an interview, Palmer said:

It’s an old ethical issue, a foundational issue, whether the ends justify the means. And people here of equal moral caliber can have different opinions. On the one hand, you can argue if the animals are mistreated and audiences are deceived, there’s no transparency, then the ends do not justify the means. It doesn’t matter how much good the film is going to do, you shouldn’t be doing it. …

The other side of the argument is the animals are only being harassed very, very slightly. The audiences don’t care if they’re being deceived. They want to sit down with a beer and, after a long day at work, enjoy the film. It doesn’t matter. They know that films are made up or full of deception—that’s what filmmaking is. And the film itself is going to promote conservation or do some social good, therefore it’s fine. …

What filmmakers have to do is weigh these arguments and make up their minds.

From my viewpoint as a scientist and a journalist, I understand the filmmaker’s dilemma. I have no problem with using captive animals, controlled settings, or fake but realistic sound to illustrate scientifically valid phenomena, but I do have concerns on the effects of filmmaking on the animals and environments affected. I have no answers, other than working to improve care of captive animals at game farms and laboratories and minimizing as much as possible the stress and/or harm to wild animals. Sometimes the ends do justify the means, other times they do not. Cases have to be decided on an individual basis.

For example, I have no problems if the lemur feeding sequence in Planet Earth was shot in a controlled environment rather than the canopy of an actual baobab tree—assuming that it was shot in a controlled environment rather than the canopy of an actual baobab tree. While I would not want to be reincarnated as a giant hawk moth in Madagascar, it was a relatively small sacrifice to pay for an increased awareness of the ecological linkages among plants, pollinators, and predators in forests and woodlands. But nature filmmakers should make a greater effort to make the audience aware of the techniques they use so that the realization that such “fakery” is employed does not result in a backlash that erodes public support for conservation efforts worldwide.

In the final chapter, Palmer offers eight suggestions for how to produce nature films that “make a difference.” They are: 1) Start with a statement of intent; 2) Work closely with reputable scientists; 3) Make conservation films that entertain; 4) Use new media effectively; 5) Disclose how the film was made and establish an ethics ranking system; 6) Practice green filmmaking; 7) Diversify the nature filmmaking community; and 8) Improve ethics training and guidelines. The suggestions are sound, although some may prove unworkable (the ethics ranking system comes to mind here). I do not get the impression that Palmer sees these recommendations as an endpoint. Rather, they are a starting point for a discussion that is needed throughout the nature filmmaking community.

Though the filmmakers are the focus of Palmer’s recommendations, I would argue that we should not absolve the public of its responsibility. The public should spurn productions that needlessly harm or harass wild animals as well as those that mistreat or feature mistreated captive animals. It should spurn shows that offer a steady diet of hysteria, hyberpole, and hocum—the staples of the sub-genre Palmer calls “nature porn and fang TV.”

The public should also be honest about what it wants. Would it watch a film featuring bears walking silently across distant rivers, or does it prefer a film with the sound of technicians splashing their hands in water in time with the bears’ steps? Public demand, as revealed by viewers’ purchasing choices in the media marketplace, exert a powerful influence over what choices are ultimately offered in that marketplace. We cannot escape our culpability in creating the world we find ourselves living in.

Current nature filmmakers should read Shooting in the Wild. Aspiring nature filmmakers should read Shooting in the Wild. More important, viewers of the work of nature filmmakers should read Shooting in the Wild. The discussion Palmer would like to have is not just for the filmmaking community. It is for all of us. For by having that discussion, and by acting on its results, we can begin to create a world that is better than the one we have.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Palmer, Chris. Personal interview. 20 Nov. 2010.

—. Shooting in the Wild: An Insider’s Account of Making Movies in the Animal Kingdom. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2010.

“Seasonal Forests.” Planet Earth: The Complete Series. Prod. Alastair Fothergill. 2006. BBC Video. 2007. DVD.

[1] The headline is misleading because some animals are set up to be eaten, which is not something I would call a “success.”

[2] While an undergraduate biology major contemplating a life as a zoologist, I changed my focus to plant geography and ecology. One of the primary reasons for the switch was my desire to avoid harming animals—no matter how necessary and unavoidable it may be—in my research.

NOTE: This is an expanded version of an essay originally written for the “History of Media, Art, and Text” class at Virginia Commonwealth University.

CLARIFICATION: I had a compulsive urge to add a reference to Palmer’s position as Distinguished Film Producer in Residence at American University’s Center for Environmental Filmmaking in the second paragraph. Given the focus of this blog is on the Mid-Atlantic region, the reference is needed to localize the post.

—30—

Leave a Response

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.